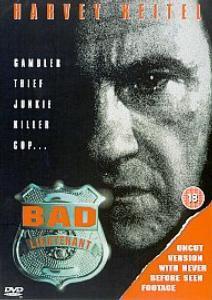

GAMBLER. THIEF. JUNKIE. KILLER. COP...

For many an artist with some sort of religious influence in their lives, at some point they will consider the topic of redemption. Rather more specifically, how far does one go before they are beyond redemption? Is that even possible? Can someone be bad for so long, but still be offered a saving grace? Does the possibility of redemption depend wholly on the amount of torment that person suffers as a result of their sins? These would be the questions that act as the central concern for Abel Ferrara’s 1992 film Bad Lieutenant, where a police officer is tormented by his own demons, but seems incapable of rectifying his mistakes.

A police Lieutenant (Harvey Keitel) goes about his day in a less than typical fashion. He has little interest in stopping or investigating crimes, but instead is more concerned with pursuing his own vices, like drugs, hookers, gambling and generally abusing his position of power. He is in serious debt, accumulated through ill bets on baseball, continuously doubling-up to recoup his losses. When a nun (Frankie Thorn) is raped in a church, the attempts to investigate the crime force the Lieutenant to reconsider his life and the choices he’s made.

Abel Ferrara is a not a subtle man, and he prides himself as someone who makes uncompromising films beyond the edge of what many believe to be proper. Released in 1976, his first feature was a porno called 9 Lives of a Wet Pussy, starring his then-girlfriend, some of her friends and about a half dozen men, which included himself, albeit reluctantly. His next film got him instant attention, particularly in the UK. His 1979 horror flick The Driller Killer wound up on the infamous ‘video nasty’ list, with the conservative populace decrying it for its amoral and corruptive influence. However, the idea of Ferrara’s work being amoral is somewhat misleading. Whilst it is true that he has a predilection for characters who are self-destructive and corrupted, and that his stories take place in a harsh, bleak world, there is still a moralistic influence that runs through his work. In fact, it’s partly because of this sense of morality that this is what cripples the characters.

Ferrara was raised a Catholic, and brought up on the streets of New York, and both of these factors figure heavily into his work. Religion is a regular thematic influence and many of his films take place on the harsh and gritty streets of his home city. In Bad Lieutenant, the film that will probably be forever regarded as Ferrara’s best, these two influences are exploited to their fullest potential. The film charts the gradual downfall of a character that has long ago receded into his own desiccated moral self, cursing his soul with every act of violence and depravity. The character is also an officer of the law, a role that is meant to reflect goodness and honour, which just makes his descent all the greater. He is never even named, credited only as The Lieutenant, marking him not as a specific individual, but as a representative of a more general corruptive authority, which is another fairly regular Ferrara preoccupation.

There is little goodness to find in this character. No goodness at all, really. Within the first twenty minutes, we see him act in ways that you’d be hard pressed to like. He yells and curses at his kids, takes bets at the scene of a double homicide that he’s supposed to be investigating, does a lot of drugs, ignores the actions of a car thief as they happen right in front of him, and engages the services of two hookers that he barely seems to notice. And this is at the highpoint of his day. Over the course of the film, he does even more drugs, loses tens of thousands of dollars on bad bets, interrupts a convenience store robbery so he can take the money himself, shoots out his own car stereo because of the baseball score, and tries to steal drugs from the scene of a crime. His most unsettling actions come from when he pulls over two young girls for a busted taillight. Neither of the girls have a licence to drive, so the Lieutenant makes them a deal: one of them strips a little bit to show her ass, and the other simulates giving a blowjob, all whilst he masturbates in front of them. And this is all in the middle of the street, albeit at night. It’s a very uncomfortable scene, made worse by the long drawn out nature of the editing. It’s also indicative as to how he operates. He steps into the situation under the guise of authority, but quickly turns this position to abusive advantage. At no point do we ever see him do anything that you could regard as good. It’s very important that we not like this man.

It’s important because we must believe him to be beyond saving, out of reach of a redemptive hand. Indeed, this is how he sees himself. Although he will identify himself as a Catholic, he must believe himself to be beyond help or hope. It’s the only way he can continue to do what he does, be what he is. However, when he hears of the brutal rape of a nun, this kicks in something of a religious crisis in him. It’s not because of the act itself. In fact, when he first hears about it, his initial reaction is to call the church a scam and say that if the victim weren’t a nun, no one would really care. What completely throws him is the reaction of the nun to her ordeal. Believing this to be an opportunity to show the divine grace of God to those that violated her, she forgives them and refuses to identify them. That their victim forgives these two rapists so quickly and without hesitation causes the Lieutenant a great deal of pain. Until now, he believed everyone to be corrupt, so he had no real need to worry about his fate. However, the nun’s actions show that there can be redemption for anyone – maybe even him. In the end, what causes the Lieutenant’s moral crisis isn’t really the toll of his wicked ways; it’s hope that breaks him. As some sort of last-ditch attempt at rebalancing his world, he goes to the nun, who he finds in the middle of prayer. Completely out of his mind on booze and drugs, he tells her that, if she tells him the identity of her attackers, he will deliver her true justice (i.e. kill them). When she refuses, he tries everything he can to get her to change her mind, pleading to her need for revenge, asking her to protect future victims, questioning her right to forgive these people for their crimes. That she steadfastly refuses to accept his offer causes him to have a complete and utter break with reality, hallucinating that Jesus now stands silently before him. There’s a line in John Milton’s Paradise Lost that goes, “abashed the Devil stood and felt how awful goodness is.” This is the root of the Lieutenant’s anguish. He now has to face the fact that for all of his power, his authority, his muscle, he is the weakest person in the film, and the thing that took him down was an act of inconceivable kindness to someone as morally repugnant as him.

Harvey Keitel’s performance in Bad Lieutenant may be one of the bravest in cinema, and perhaps the best of his career. He engages fully with hideous nature of the Lieutenant, tackling it all without fear or hesitance or judgement. He’s a violent man, a hypocrite and an utterly reprehensible human being… and Keitel holds nothing back from his performance. It’s not just in the harsh nature of the character that Keitel excels, but in the searing anguish that sits at his centre. When he finally breaks down in the church, crying and yelling at the image of Jesus in front of him, his pained sobs show just how lost and devastated he is. Keitel is on absolute fire in this film, and should probably receive way more credit than he actually does for his work here.

As to the concerns about religion and morality, that’s something worthy of a bit more discussion. It would seem that Bad Lieutenant proposes the idea that Catholicism is the saviour. Although the nun is not protected by her status or position in society, it’s her calling that allows her to deal with her trauma. Indeed, she is the one with most justification to be angry, but she chooses to follow her faith to help her cope. The nun is really the only character in the film that isn’t a hypocrite. Whilst that is rather commendable to a degree, it does start to get a little uneasy in other areas.

The rapists, having been forgiven for their crimes, receive no punishment. In fact, what they receive is protection. With their victim having forgiven them and prayed for them, they do indeed seem to find protection and help. The Lieutenant, being the bad soul that he is, finds his situation becoming darker and more insurmountable as he goes on without asking forgiveness from those he wronged. Therefore, his fate is sealed. There’s also a sense in the film that there exists two laws: those of Man and those of God. The former laws are shown to be hollow, weak, being enforced by the whims of the flawed people that wear the badge; the latter laws are stronger, have more resonance, are represented by individuals of character and grace. From this perspective, it seems to espouse an idea that can be found in some of the very devout – that by following the laws of God, you don’t need to fear the laws, or actions, of Man. This has never been an idea to sit too well with me, since religious rules are as open to interpretation as the rest of them. Plus, it’s this kind of thinking that can lead people to kill doctors who work in women’s clinics because they believe it’s their moral responsibility to protect the unborn. As such, I really can’t take to the ideas presented in this film.

Bad Lieutenant is a raw, gritty, powerful and unsettling film, with an absolutely superb performance from Harvey Keitel at its core. Those looking for a good story may be somewhat disappointed, since the film more follows the apparently disjointed actions of a severely unhinged character rather than an actual narrative. However, the character is thoroughly intriguing in the most hideous terms. The heavy-handed use of religious iconography in the film can lead to some uncomfortable conclusions, but it does at least present an opportunity to engage with these ideas. It’s not for everyone, but it is something that should perhaps be experienced once, if for no other reason than to appreciate the great skill of the central performer.

No comments:

Post a Comment